Way back in the year 2000, I started working full-time as an English lecturer at an engineering university in Japan. Coming up to the end of my first year, there was a buzz phrase that was doing the rounds and it seemed to be the focus of many of our meetings – it was “Media English”. No one really knew what it meant, but there were grants available and that always generates interest.

It was decided that a textbook should be written based around this rather vague idea of Media English, and that it should be written by a committee of 11 English teachers. There is an old saying that I often remember when I am in meetings: “The IQ of a group is equal to the IQ of the lowest member, divided by the number of people in the group.” I generally like working on projects either on my own or with just a couple of people, so our endless committee meetings, which stretched on for months, were driving me crazy. Every week we would sit around with long, vague, and unfocused discussions about the nature of Media English. There was very little practical sense about how to convert these discussions into concrete lessons – lessons which would ultimately be used to help students in a classroom.

Eventually, I got impatient and after one particularly long and pointless meeting, I spent several intensive days in my office and put together three sample units. My goal was to introduce these to the committee and hopefully move things forward in a more focused manner. I had just finished my Masters in TESOL and was all fired up with ideas about teaching and materials development. When I showed them to the committee in the next meeting, the members were so impressed that someone had actually done something that I was asked if I wanted to do it all. Of course, many of the members were happy to have an escape route from something that they didn’t really want to be involved in. For me, the choice between endless committee meetings and creating materials was an easy one. I immediately said that I would be happy to do it all myself. At the time, I didn’t realize the hundreds of hours it would consume, or how it would change my life in many ways, but I am glad to have made that decision all those years ago.

Deciding the first few topics for the textbook wasn’t so difficult. Many EFL texts have similar headings such as Food, Health, and the Environment. I had been using other textbooks like Interchange, and was influenced and informed by their well thought out design, so these common topics made it into the textbook I was creating, too. I realized that these themes are common and used often because they are interesting for all people, regardless of where they live. Everyone has to eat, take care of their health, and wants to live in a nice environment. These are important aspects of our humanity, and it was from these kinds of topics that the first half of the title of my textbook “Humanity and Technology” came about.

But this textbook was to be used to learn English in an engineering school, and I also knew engineers well. I graduated with a degree in civil engineering, and worked for several years as an engineer at a Japanese company. Engineers are practical and they have a genuine interest in science and technology. And that is where the second half of the title for my textbook came from. So, the book title was set, and Humanity and Technology really began to take shape.

I recognized that the four skills of language learning needed to be a part of each unit. For the general topics like Food and Health, I created content that included popular science and technology within the reading and listening activities. I also incorporated topics of more specific interest to students who had a focus on science and engineering with units such as “History of Science and Technology”, “The Future”, and “Robots and Artificial Intelligence.” I made sure that each unit also provided ample opportunities for students to speak to each other, as well as write down their own ideas. Choosing the topics determined the framework of the entire book, and the 12 units reflect the amount of content and learning that can be carried out by Japanese students within one year of English classes, or the equivalent of about 30 to 32 weeks.

Within each unit of the book, there also needs to be a clear structure. Teachers and students both need a clear and consistent format within each unit so that the time can be spent effectively on learning rather than explaining activities. There are 13 learning activities in each unit, which provides abundant choice for teachers to meet the needs of their students. These activities were influenced by other textbooks that I had been using and through my own experience of what works well with Japanese students. It includes standard activities such as vocabulary, “Starting Out” (for activating schemata and previous knowledge), reading exercises, listening in various forms, and conversation activities which included practice of conversation strategies. I also came up with my own original activity types to meet the needs of the students, and I am still proud of how well these activities have worked over the years.

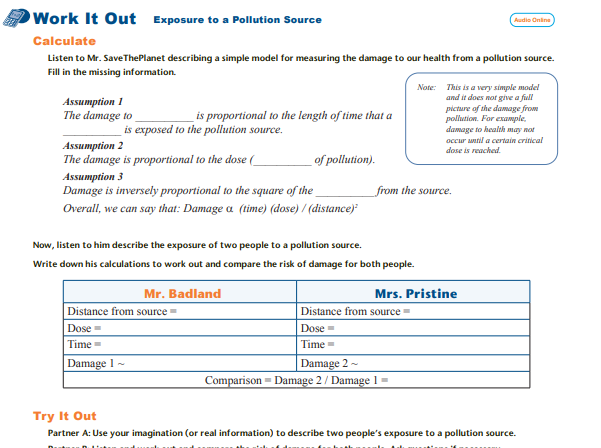

For example, in the “Work It Out” activities, the students listen to a speaker talk about a topic. They then use the information they have just listened to in order to calculate the answer to a mathematical problem. Students love this kind of activity, and the bonus is that in order to find the correct answer, they are really motivated towards focused listening.

In “Reading Exchange,” students read a short passage aloud to their partner, who in turn is listening for the correct answers to their questions while their partner reads.

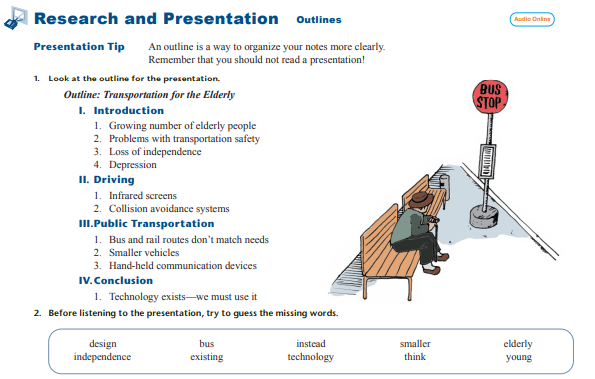

In “Research and Presentation,” students listen to short model presentations. For homework, they then carry out some simple research on their own chosen aspect of the topic and make a short presentation in the next class. I tried to tie these into the topic of the unit and to provide useful but simple presentation tips that students could follow. There were already lots of books dedicated to presentation skills, but I felt that providing a decent research and presentation section in every unit of a more general textbook was good for engineering and science students. These presentations became the highlight of the course for many students and teachers.

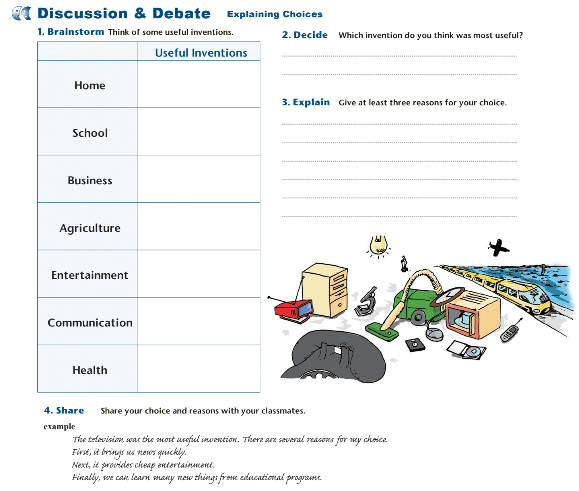

In “Discussion and Debate,” students address the ethical implications of technology in society and the environment. This was a buzzword at the time, and I think that this concept has held up really well over the years. While traditionally engineers and scientists were not expected or required to think about the ethical implications of their work, this has clearly changed. The use of technology in society has caused massive changes from climate change to the psychological effects of overuse of smartphones. These kinds of discussion give students excellent practice in beginning to think critically about these important issues.

I finished the pilot edition of Humanity and Technology in 2001 and it was such a cute hand-made book with illustrations which bore little relevance to the text itself, but certainly made it look nice. At the time, I used the ClarisWorks program from Apple which has long since disappeared. To put it mildly, it was not the best program for layout and I learned a lot. I had it printed out at a local printer and we hired some students to sell the books.

The following year, Intercom Press agreed to publish the first official edition of Humanity and Technology. Working with an experienced editor added so much to the activities and content of the book. Beginning authors often underestimate the value of a good editor who can offer new perspectives and ideas, as well as provide their own expertise and finesse to round out and complete any given text. A good-looking textbook has a definite appeal. For Humanity and Technology, the layout was prepared in the standard design program of the time, Quark, and along with a beautiful cover it all came together to make the textbook that much more appealing. We put out the 2nd edition in about 2007, and improved the book greatly based on teacher suggestions. Taking the time to get input from the teachers who are using your text is an invaluable resource in the world of textbook creation – be sure to know who is using your book in order to get important feedback, critiques and possible corrections for the typographical errors that are bound to slip by even the keenest editor’s eye.

By 2018, the book was fading away and hardly being used. It had definitely become dated. Intercom Press asked for a new edition and PAWS International became a co-publisher. The 3rd edition was a mammoth undertaking. Some topics such as Food hadn’t changed enormously over the years, but others such as the Internet, City Life, Robots and Artificial Intelligence, and The Future had changed beyond recognition. The first two editions predated social media and many people still did not even have Internet access! Making the 3rd edition took hundreds of hours, but it was finally published in full colour and it is right up-to-date with sections on bitcoin, nanotechnology, and much more!

Humanity and Technology was my first textbook. Since then, I have authored or edited almost 40 textbooks, but it still holds a very special place in my heart – my own little tribute to the wonders of both humanity and technology.

If you would like to see an inspection copy of Humanity and Technology for consideration for your students, please contact us.