by Eric Gondree, author of Journey to America Today

As a kid, I remember becoming truly interested in the portions of Sesame Street in which Big Bird managed to learn a few new Spanish phrases from his neighbors Maria and Luis. The idea of being able to speak another language, communicating with people beyond the reach of English, was something that I found terribly engrossing. Additionally, I suppose I was lucky enough to have parents who supported me in studying language outside of school.

Later on, I started to notice how learning about foreign history and culture could be very linked to study of foreign language. I casually dabbled in Russian starting in 5th grade and around the same time, I’d gotten my hands on a well-illustrated British guidebook to the city of Moscow. Being able to learn about the names of places, streets, subway stations and so on helped me learn plenty of new vocabulary as well. It also helped me learn a lot about Russian culture. A grammar textbook wouldn’t necessarily be able to teach you that one of the Moscow suburbs, Ostankino, is nationally-known because it’s the site of an important television studio. Or that many Russian cities have a street named after Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space.

This might’ve seemed like trivia or factoids for part of the time– and some of it certainly was– but knowing more about a culture really can allow a learner to use the information as a part of their communication. This seems like an obvious plus if they wish to go into activities like studying abroad or enriching their experience when visiting culturally-important places. If looking at films, literature and music can enrich one’s study of a foreign language, it seemed likely to me that history could be an additional strand which could be tied in. At that time, little did I know that the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) movement in language education was predicated on precisely that idea. CLIL aims to integrate content and language learning through the 4 C’s: Content, Communication, Cognition, and Community/Culture.

History is definitely a valuable component of CLIL and the history of America is a fascinating story that forms the basis of Journey to America Today. After several years of teaching Japanese university students, I sometimes wondered what they’d previously learned about world history and how it was taught to them. I found myself asking other teachers questions on Japanese high school curricula and I often felt as if I didn’t know what they didn’t know. If you don’t see the modern world as having been shaped by larger historical processes, seeing the international news would simply be bewildering. For instance, how could one start to make sense of the Black Lives Matter movement? Or Brexit? Or protests in Hong Kong? Or any other complex problem? It is only by understanding the history behind the situation that students can begin to understand the situation today.

Over time, I really felt the desire to develop a real U.S. history class for university students in Japan. I also felt that since I’d seen a decent number of effective history textbooks (and read a lot of criticism about the not-so-good textbooks), I felt that I was ready to create teaching materials on my own. The textbook Journey to America Today was an expansion of a collection teaching materials, learner resources and discussion activities that I had created and accumulated over the years.

Selecting Topics

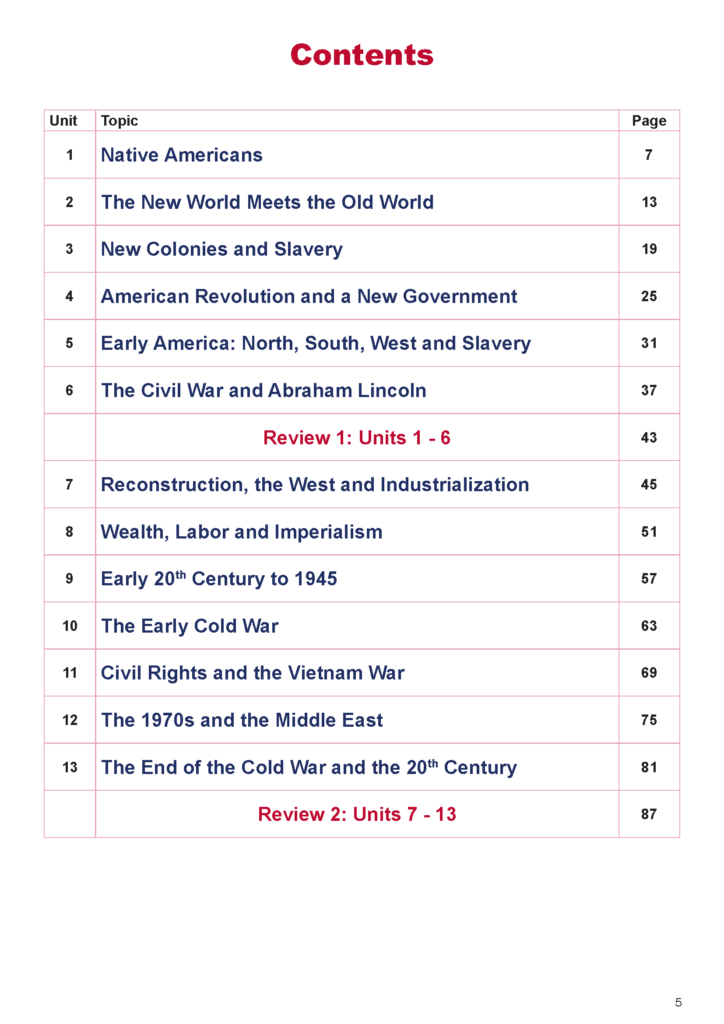

Journey to America Today is divided into 13 Units so it can fit into a 15-week college or university semester with enough time to accommodate reviews or supplementary activities (like movies or project days). It is also suitable for a one-year university course by supplementing it with additional sources such as videos or readings, or extending the research and presentation activities.

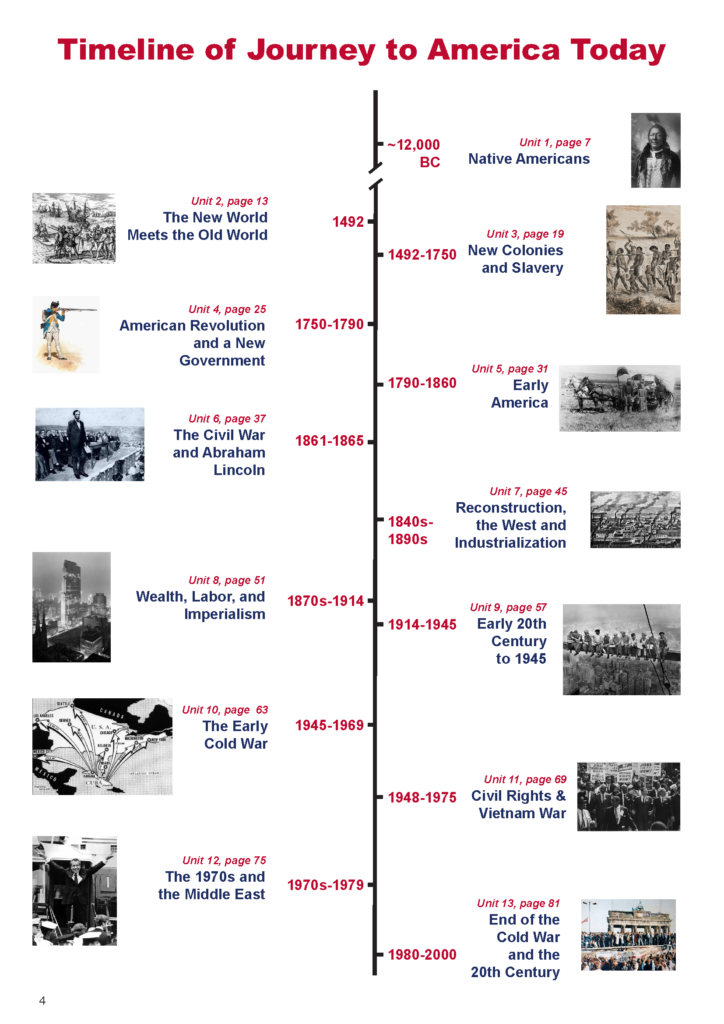

The Units are arranged chronologically (with some overlap) to represent approximate periods and the passage of time up to the year 2000. All dates take place within the Christian Era (CE). In each reading, important concepts are underlined. The timeline on page 4 of the textbook gives a graphic overview of the historical eras covered. Each unit introduces American history and will help students to understand America today.

Due to size limitations, there were unfortunately many important topics which could not be included. A great many items, (the Electoral College, the War of 1812, the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, etc.) go unmentioned. Similarly, I would have preferred to include more about the women’s suffrage movement, the experiences of immigrants, the movements for gay rights, and many other things. Because history represents a reconstruction of the past, any attempted reconstruction is going to be necessarily selective, and I encourage all teachers (and students!) to think critically and read many other good sources of information to learn more. The teacher guide also includes many useful links to online sources which can be useful for you and your students.

Learning Activities

An important priority was adapting the narrative to teaching English and creating useful and effective teaching activities. Japanese students have sometimes told me that their history classes were their least favorite classes. And I can’t really blame them for that. Social studies is often considered one of the least popular subjects among students in the U.S. as well. So clearly, it was important to create engaging activities that would make the learning interesting and enjoyable for students. Fortunately, as the CLIL movement has shown, learning about foreign culture and history can be a fruitful way to teach language.

As I worked on obtaining my master’s in education for TESOL, I also worked on a parallel effort to become certified to teach Social Studies as a substitute schoolteacher. In the process of doing so, I learned a lot of Social Studies-teaching techniques which also proved to be quite effective. I’d also found a wealth of resources online for teachers who wished to create engaging, interesting classes for their students. If a teacher is required to start from scratch, there is a lot of help available.

Journey to America Today began from materials used in several of my U.S. culture-themed electives and then utilizing the skills that I had learned through social studies and TESOL, I developed a range of learning activities that aim to keep students engaged and interacting with the content throughout the course. The image below shows a summary of the main activities in each unit of the textbook.

I have been very pleased by the positive feedback on Journey to America Today from both students and teachers. I have always experienced great fulfillment from learning from history and learning from language, and my hope is to share the same kind of fulfillment with those who enjoy doing either (or both!).

Although this is a small book, it feels like a big personal accomplishment. I would like to thank PAWS International for giving me this opportunity. I am also thankful that I have learned much from the many great students and talented teachers that I have met in Japan, in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world. Finally, I would like to thank Mari for the love, hard work, encouragement and ideas that she has given me over many years.

If Journey to America Today can help even a small number of students to exit class with a sharpened interest in the world around them in addition to improved English skills, then I consider that to be a success.

Please check out the webpage for the textbook Journey to America Today. You can also request an inspection copy if you would like to consider using it with your students.